Sándor Ferenczi was born on 7 July 1873 in Miskolc, Hungary. His father, Baruch Fraenkel (1830-1889), migrated with his family from Cracow to Hungary and fought in that country’s War of Independence against Austria in 1848-‘49. He trained for a career in the book trade, running his own shop as of 1856. His second wife, Rosa Eibenschütz, was brought up in Vienna. Owing to the parents’ own history, the family was multilingual, speaking Hungarian, German, Yiddish and Polish. Ferenczi himself was bilingual (Hungarian and German) and would later learn English and French. Sándor was born the eighth child among 10 brothers and sisters in this liberal, middle-class, Jewish family. As an expression of his assimilation into Hungarian society, his father Hungarianized the family name from Fraenkel to Ferenczi.

The family book shop played a significant role in the cultural life of the city. Not only did it deal in bookselling and lending, but also in publishing as well as promoting culture in the town, an endeavour in which Ferenczi’s mother also played an important part. Famous poets, writers and artists would come to the shop, sparking Ferenczi’s interest and contributing to the forming of later friendships (Harmat, 1994; Kapusi, 2000).

The family book shop played a significant role in the cultural life of the city. Not only did it deal in bookselling and lending, but also in publishing as well as promoting culture in the town, an endeavour in which Ferenczi’s mother also played an important part. Famous poets, writers and artists would come to the shop, sparking Ferenczi’s interest and contributing to the forming of later friendships (Harmat, 1994; Kapusi, 2000).

After completing secondary school, Ferenczi studied medicine in Vienna, receiving his medical degree in 1894. During the Viennese years, he was greatly influenced by Richard von Krafft-Ebing’s ideas on sexual disorders, Darwin’s theory of selection and Jean-Batiste Lamark and Ernst Haeckel’s teachings on the link between philogenesis and ontogenesis (Ferenczi, 1900/1999) While in Vienna, although he read Freud and Breuer’s studies on the pathogenesis of hysteria, he disliked them so much that he forgot about them for years (Ferenczi, 1908/1980).

Ferenczi’s first post in Budapest was at the St. Rókus Hospital in a ward that dealt with prostitutes and patients suffering from venereal disease – work that he did not enjoy. As a consolation, he began dealing with phenomena which fell outside the area of conscious functions (automatic writing and spiritism). It was during this period that he met internist Lajos Lévy and psychiatrist István Hollós with whom he had lifelong professonal relationship. Through Lévy’s mediation, he came in contact with the man who would become the patron of his early years, Miksa Schächter, owner and editor-in-chief of the weekly medical journal Gyógyászat [Therapy]. He published Ferenczi’s early writings and would later make the ideas of psychoanalysis available to physicians as that field began to grow. Between 1897 and 1908, before Ferenczi came to know Freud and psychoanalysis, he published 98 papers, case studies, essays and book reviews. He dealt primarily with unconscious and semi-conscious states – hypnotism, dreams and occult phenomena – but he was also interested in neurological diseases, psychological experimentation and links in the psyche to sexuality. He considered a relationship founded on doctor-patient co-operation essential to curing the patient; this flew in the face of the generally held view of the day and challenged expressions of hierarchy and authority in the medical community. The approach that would later characterise him as a psychoanalyst was already taking shape in his early writings (Mészáros, 1999, 2023).

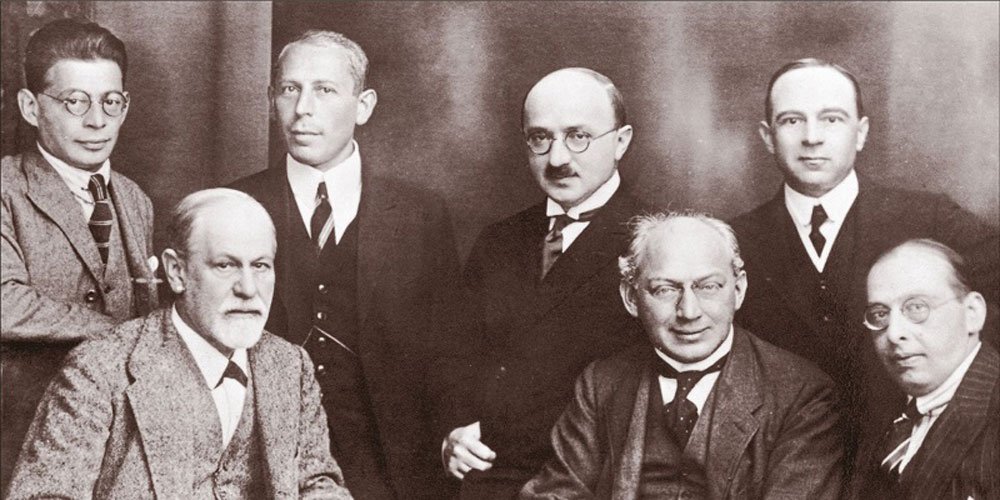

After Ferenczi met Freud in early 1908, an intense lifelong relationship was forged between them, both personal and professional. Ferenczi immediately committed himself to psychoanalysis. He soon published the first work to reflect the perspective of early object relations theory. In addition to projection, Ferenczi described introjection (Ferenczi, 1909/1999). 1910 saw the publication of his first volume of psychoanalytic writings (Ferenczi, 1910, 1914, 1919). Ferenczi spared no effort in promoting the development of the psychoanalytic movement. Ferenczi proposed to establish the International Psychoanalytical Association in 1910 and later he saw it as his most „enduring” (Ferenczi, 1928/2006, p. 206). contribution to the history of psychoanalysis. He urged on the founding of the International Journal of Psychoanalysis (in 1920), and also founded the Hungarian Psychoanalytical Society in 1913, and remained its president until his death in 1933.

It was through Ferenczi’s interdisciplinary openness and his efforts to popularise psychoanalysis that the discipline found its way into the ranks of physicians, social scientists and other inquiring minds. It established ties to the fields of literature, pedagogy, ethnography and the arts as well as intertwining with Hungarian intellectual movements such as those of the progressives and middle-class radicals. A new audiences were exposed to psychoanalysis through literary journals such as Nyugat [West], which was founded by Ignotus, a friend of Ferenczi’s and a leading figure in modern Hungarian literature. In his writings, Ferenczi also emphasised ideas of radical social critique (Ferenczi, 1908/1999; 1914/1980.).

During the First World War, Ferenczi served as an army physician and, based on his own experiences there, elaborated the approach of psychoanalysis to the development of war neuroses and their treatment (Ferenczi, 1919/1980; Harris, 2015). This represented one of the primary topics at the 5th International Psychoanalytical Congress held in Budapest in the final months of the war. Ferenczi was elected president of the IPA at the congress. Shortly before the end of the war, in October 1918, the Austro-Hungarian war command issued an order that recommended the use of psychoanalysis at military psychiatric facilities.

Between 1918-1920, Hungary witnessed a series of socio-political changes that left an indelible mark on the psychoanalytic movement there. With the collapse of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, travel and communication between the countries of Central Eastern Europe became difficult and thus Ferenczi saw the need to resign from the IPA presidency in 1919.

In April 1919, during the short-lived Hungarian Soviet Republic – and based on an earlier initiative by medical students – Ferenczi was granted a professorship and a department of psychoanalysis was established within the Budapest university’s Faculty of Medicine. This represented the first time that psychoanalysis became fully integrated into a medical curriculum. However, after the fall of the Soviet Republic later in 1919, Ferenczi was removed from his post and psychoanalysis lost its place within higher education. (Erős, 2011). An important change was also brought about in Ferenczi’s personal life. After a relationship of almost twenty years, he married a woman named Gizella Pálos (Berman, 2004).

The ensuing White Terror at the start of the right-wing Horthy regime set off a first wave of emigration from Hungary, involving a number of current and future analysts. Many of them, such as Sándor Radó, Melanie Klein, Margaret Mahler, Michael Balint, Alice Balint and Franz Alexander, settled in Berlin or Vienna.

From the 1920s, the technique of psychoanalysis and an increase in therapeutic effectiveness became Ferenczi’s top priorities. With countertransference having previously been thrust into the background, Ferenczi now put it in the service of psychoanalysis so that the psychoanalytic relationship became a two-way process through the transference-countertransference dynamic (Ferenczi, 1919/1980, 1928/1980; Aron and Harris, 1993, Martín Cabré, 1998, Mészáros 2004), and Ferenczi became “the founder of all relationship-based psychoanalysis” (Haynal, 2002 p. xi).

He experimented with active technique as he did later with mutual analysis. He eventually set aside both techniques, but these experiments greatly contributed to the development of psychoanalytic theory and practice (Haynal, 1988, Borgogno, 2007a). He recognised that an analyst’s work depended on participation in training analysis lest his/her own unresolved issues hinder work with the patient. Thus, Ferenczi initiated the establishment of a systematic training program. He focused attention on the significance of the early mother-child relationship and on parental responsibility in the development of the personality (Ferenczi, 1929/1980).

Between 1926 and 1927, Ferenczi held lectures in New York City at the invitation of the New School for Social Research and in Washington, D.C. at the invitation of societies. These lectures had an influence on early interpersonal psychoanalysis, key figures of which would maintain personal contact with him, such as Harry Stack Sullivan and later Clara M. Thompson (Silver, 1996). Ferenczi was a strong advocate of lay analysis, a fact that drew fierce criticism. After his return to Budapest, he continued analysing of difficult cases (Fortune, 2007; Brennan, 2015; Rachman, 2015; Rudnytsky, 2015) and focused on understanding more about early mother-child relationship and trauma. He placed the trauma within a system of interpersonal and intrapsychic sequence of processes between victim and persecutor that pushed the process of traumatisation toward dimensions of object relations, and emphasased that trauma is based on a real event (Ferenczi, 1932/1988; Ferenczi, 1933/1980). Ferenczi describes a new ego-defence mechanism as identification with the aggressor (Ferenczi, 1933/1980), that became widely known as Stockholm Syndrome in 1973. His concept of trauma led to new approaches that would later emerge in the complex system of modern trauma theory and therapy. (Dupont, 1998; Bonomi, 2004; Borgogno, 2007b; Frankel, 1998; Mészáros, 2010; Vida, 2005)

Ferenczi’s initiatives can also be recognised in the development of the perspective of the Budapest School. (Mészáros, 2000, Szekacs-Weisz and Keve, 2012; Meszaros, 2014). The 1920s and ‘30s were marked by the application of the countertransference perspective (Michael Balint, Alice Balint, Therese Benedek and Fanny Hann-Kende), by a focus on the early mother-child relationship and on psychoanalytic psychosomatics (Lajos Lévy, Michael Balint and later Franz Alexander) as well as by an interdisciplinary spread of the psychoanalytic way of thinking, e.g. in the creation of psychoanalytic anthropology (Géza Róheim). All of these had influenced modern psychoanalysis after the emigration of the Budapest psychoanalysts in the 1920s and during the Nazi years. Ferenczi’s relationship with Freud deteriorated during the last years of his life. Conflicts developed which were painful to both of them (Freud-Ferenczi, 2000). Ferenczi died unexpectedly of pernicious anaemia prior to his 60th birthday. For several decades, the rumour spread by Ernest Jones of Ferenczi’s mental illness played a powerful role in preventing Ferenczi’s ideas from taking their rightful place in the history of psychoanalysis (Jones, 1957; Bonomi, 1998).

International reseaches and publications in the last 30 years integrated Ferenczi into the maistream and proved that his theoretical and therapeutic contributions made him as the most significant forerunner to modern psychoanalysis.

Judit Mészáros

References:

Aron, L., & Harris, A. (Eds.) (1993). The Legacy of Sándor Ferenczi. Hillsdale, NJ: The Analytic Press.

Berman, E. (2004). Sándor, Gizella, Elma. The International Journal of Psychoanalysis, 85: 489–520.

Brennan, B. W. (2015). Out of the Archive/ Unto the Couch: Clara Thompson’s Analysis with Ferenczi. In: The Legacy of Sándor Ferenczi. From Ghost to Ancestor. Ed. Adrienne Harris & Steve Kuchuck, Routledge: London, pp. 77-95.

Bonomi, C. (1998). Jones’s allegation of Ferenczi’s mental deterioration: A reassessment. International Forum of Psychoanalysis, 7: 201–206.

Bonomi, C. (2004). Trauma and the Symbolic Function of the Mind. International Forum of Psychoanalysis, 13: 45–50.

Borgogno, F. (2007a). Psychoanalysis as a Journey. London: Open Gate Press.

Borgogno, F. (2007b). A contribution by Ferenczi to child psychoanalysis: the trauma and the traumatic – are they thinkable? In: Psychoanalysis as a Journey. London: Open Gate Press. pp. 171–186.

Dupont, J. (1998). The concept of trauma according to Ferenczi and its effects on subsequent psychoanalytical research. International Forum of Psychoanalysis, 7: 235–240.

Erős, F. (2011). Pszichoanalízis és forradalom. [Psychoanalysis and Revolution]. Jószöveg Műhely: Budapest.

Ferenczi, S. (1900/1999). Öntudat, fejlődés Consciousness, development]. In: J. Mészáros (Ed., Intr., & Epilogue), Ferenczi Sándor: A pszichoanalízis felé. Fiatalkori írások 1897-1908. [Toward Psychoanalysis. Early Papers 1897-1908]. Budapest: Osiris, pp. 45–48.

Ferenczi, S. (1908/1980). Actual and Psycho-neuroses in the light of Freud’s investigations and psycho-analysis. In: Further Contributions to the Theory and Technique of Psychoanalysis. London: Hogarth, 1959 (reprinted London: Karnac, 1980), pp. 30–55.

Ferenczi, S. (1908/1999). Psychoanalysis and education. In: Selected Writings. Ed., and introduction by Julia Borossa. Penguin Books, London, pp. 25-30.

Ferenczi, (1909/1999). Introjection and Transference. In: Selected Writings. Ed. and introduction by Julia Borossa. Penguin Books, London, pp. 31-66.

Ferenczi, S. (1910). Lélekelemzés. Értekezések a pszichoanalízis köréből (S. Freud előszavával). Psychoanalysis. Psychoanalytic studies. Foreword by S. Freud Szilágyi Béla, Budapest.

Ferenczi, S. (1914). Ideges tünetek keletkezése és eltűnése és egyéb értekezések a pszichoanalízis köréből. [The Origin and Disappearance of Nervous Symptoms.] Dick Manó, Budapest.

Ferenczi, (1914/1980). On psychoanalysis and its judicial and sociological significance. A lecture for judges and barristers. In: J. Rickman (Ed.), Further Contributions to the Theory and Technique of Psycho-Analysis. London: Hogarth, 1959 (reprinted London: Karnac, 1980), pp. 424–434.

Ferenczi, S. (1919). A hisztéria és a pathoneurózisok. Pszichoanalitikai értekezések. Hysteria and Pathoneuroses. Psychoanalytic Studies.], Dick Manó, Budapest.

German: Hysterische- und Pathoneurosen. (The same as the Hungarian edition, with the exception of the article: “Die Psychoanalyse der Kriegsneurosen”) Internationaler Psychoanalytischer Verlag, Wien.

Ferenczi, S. (1919/1980). On the Technique of Psycho-Analysis. In: Further Contributions to the Theory and Technique of Psycho-Analysis. London: Hogarth, 1959 (reprinted London: Karnac, 1980), pp. 177–189.

Ferenczi, S. (1928/1980). The elasticity of psycho-analytic technique. In: M. Balint (Ed.) Final Contributions to the Problems and Methods of Psycho-Analysis. London: Maresfield Reprints, pp. 87-101.

Ferenczi, (1929/1980). The Unwelcome Child and his Death-Instinct. The International Journal of Psychoanalysis, (10) 1929, 125-129. In: Final Contributions to Psychoanalysis. 102–107. The Unwelcome Child and his Death Drive. (1999) Selected Writings. Ed. and introduction by Julia Borossa. Penguin Books, London, pp. 269-274.

Ferenczi, (1928/2006). A szerelem végső titkai [The ultimate secrets of love]. Thalassa, 17(2-3:203-206.

Ferenczi, S. 1932. The Clinical Diary. (Ed. J. Dupont). Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press.

Ferenczi, S. (1933/1980). Confusion of tongues between adults and the child. In: M. Balint (Ed.), Final Contributions to the Problems and Methods of Psycho-Analysis. London: Maresfield Reprints, pp. 156–167.

Fortune, C. (2007). Sandor Ferenczi’s Analysis of ‘R.N.’: A Critically Important Case in the History of Psychoanalysis. British Journal of Psychotherapy, 9 (4):436 – 443.

Frankel, J. (1998). Ferenczi’s trauma theory. The American Journal of Psychoanalysis, 58:41-61.

Freud, S., & Ferenczi, S. (2000). E. Brabant, E. Falzeder, & P. Giampieri-Deutsch (Eds.), P. Hoffer (Trans.), [With an Introduction by Judith Dupont]: Correspondence, Volume 3, 1920-1933. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Harmat, P. (1994). Freud, Ferenczi és a magyarországi pszichoanalízis [Freud, Ferenczi, and Hungarian psychoanalysis]. Budapest: Bethlen Gábor Könyvkiadó.

Harris, A. (2015). Ferenczi’s Work on War Neurosis. In: The Legacy of Sándor Ferenczi. From Ghost to Ancestor. Ed. Adrienne Harris & Steve Kuchuck, Routledge: London, pp. 127- 133.

Haynal, A. (1988). The Technique at Issue. Controversies in Psychoanalysis from Freud and Ferenczi to Michael Balint. London: Karnac.

Haynal, A. (2002). Disappearing and Reviving. Sándor Ferenczi in the History of Psychoanalysis. London: Karnac.

Jones, E. (1957). The Life and Work of Sigmund Freud. Volume 3. The Last Phase 1919-1939. London: The Hogarth Press.

Kapusi, K. (2000). A gyermek Ferenczi Sándor és családjának miskolci története [The Miskolc story of young Sándor Ferenczi and his family]. In: I. Dobrossy (Ed.), Levéltári évkönyv [Archives Annual], 10, Miskolc, 67–86.

Martín Cabré, L. J. (1998). Ferenczi’s Contribution to the Concept of Countertransference. International Forum of Psychoanalysis, 7: 247–255.

Mészáros, J. (Ed., Intr., & Epilogue) (1999). Ferenczi Sándor: A pszichoanalízis felé. Fiatalkori írások 1897-1908. [Sándor Ferenczi: Toward Psychoanalysis. Early Papers 1897-1908]. Budapest: Osiris.

Mészáros, J. (Ed., Preface & Epilogue) (2000). In Memoriam Ferenczi Sándor. Budapest: Jószöveg.

Mészáros, J. (2010). Building Blocks Toward Contemporary Trauma Theory: Ferenczi’s Paradigm Shift. The American Journal of Psychoanalysis, 70: 328–340.

Meszaros, J. (2014). Ferenczi and Beyond: Exile of the Budapest School and Solidarity in the Psychoanalyic Movement during the Nazi Years. London: Karnac.

Mészáros, J. (Ed., Intr.,) (2023). Ferenczi a pszichoanalízis felé. Preanalitikus írások 1897 – 1908. Ferenczi Sándor összes művei 1. kötet. [Ferenczi toward psychoanalyis. Preanalytic papers 1897 – 1908. Complete works of Sándor Ferenczi, Vol. 1.] Budapest: Oriold és Társai.

Rachman, A. Wm. (2015). Elisabeth Severn: Sándor Ferenczi’s Analysand and Collaborator in the Study and Treatment of Trauma. In: The Legacy of Sándor Ferenczi. From Ghost to Ancestor. Ed. Adrienne Harris & Steve Kuchuck, Routledge: London, pp. 111- 126.

Rudnytsky, P. L. (2015). The Other Side of the Story: Severn on Ferenczi and Mutual Analysis. In: The Legacy of Sándor Ferenczi. From Ghost to Ancestor. Ed. Adrienne Harris & Steve Kuchuck, Routledge: London, pp. 134-149.

Szekacs-Weisz, J and Keve, T. (Eds.) (2012). Ferenczi and His World: Rekindling the Spirit of the Budapest School. London, Karnac.

Silver, A.-L. (1996). Ferenczi’s Early Impact on Washington, D. C. In: P. L. Rudnytsky, A. Bókay, & P. Giampieri-Deutsch (Eds.), Ferenczi’s Turn in Psychoanalysis. New York: New York University Press, pp. 89–106.

Vida, J. E. (2005). Treating The “Wise Baby”. The American Journal of Psychoanalysis, 65: 3–12.